Modular Life: Benchmarks

In the second article in the series, we’ll try to gauge the relative speeds of running the same code compiled to native versus WASM running outside of the browser. While the benchmark outlined below does not capture all of the aspects of language performance, it can at least give us a ballpark estimate of the relative speeds.

The code used for this article can be found on GitHub.

Triangle Number

For this benchmark, we will compare the sequential read and write performance between native Rust and WASM. A simple way to achieve that is to first write monotonically increasing numbers to each memory location in turn. Then, go over the full range of memory, this time summing them all up. This summing operation has minimal computational complexity and therefore emphasizes the pure read speed. As I discovered while writing this, summing the numbers between 1 and n is actually called the nth Triangle number. This is useful as there is an equation to calculate the triangle number efficiently and we can use that to verify our calculation.

$$ T_{n} = \frac{n(n+1)}{2} $$

So, let’s load up some memory and calculate a large triangle number in the least efficient way possible! Please note that the n above and side length of the equilateral triangle are equivalent. Therefore, we will use a side length of 67,108,864 ($2^{26}$) and unsigned 64-bit values, which in total consumes 512 Mi of memory. This side length was chosen primarily on the basis of it taking a while to process and also that it fits nicely into a standard power-of-two memory allocation. The 64-bit integer size was chosen because the triangle length of a number that large overflows 32-bit integers.

WASM comes with unavoidable overhead in that it needs a virtual machine to execute it and the language enforces memory safety by checking bounds, so it should lag behind native performance to some degree. So how much performance is WASM leaving on the table ? Is it 50% slower? 100%? Let’s find out!

The Program

First, let’s start by writing the series of integers we’ll need to calculate the triangle number into a Vector.

This will serve as our write benchmark.

Please note that we will capture the performance statistics using a benchmark framework.

The main function here is more for illustrative and testing purposes.

/// Create a series that contains the integers from `1` to `side_length`

fn create_triangle_number_series(side_length: u64) -> Vec<u64> {

// `=side_length` makes the range inclusive

(1..=side_length).collect()

}

fn main() {

const SIDE_LENGTH: u64 = 67_108_864;

let series = create_triangle_number_series(SIDE_LENGTH);

}

Next, let’s sum the series and capture how long that operation takes. This is the read portion of our benchmark.

/// Sum up all of the values in the series

fn sum_series(series: &[u64]) -> u64 {

series.iter().sum()

}

fn main() {

// ...

// sum the series and capture how long it took

let start = Instant::now();

let sum = sum_series(&series);

let duration = start.elapsed();

}

Finally, let’s ensure that we’re getting the right answer compared to the formula.

/// Calculate the triangle number using the formula

///

/// The formula is `n*(n+1)/2`, where `n` is the side length

fn calculate_triangle_number(side_length: u64) -> u64 {

(side_length * (side_length + 1)) / 2

}

fn main() {

// ...

// compare our summed series against the "real" calculation

assert_eq!(sum, calculate_triangle_number(SIDE_LENGTH));

}

Let’s take a look at the final main function, including the output of microseconds (µs) that the summation operation took. We are using microseconds here to get a more precise measurement of the run timings.

// Calculate the triangle number

fn main() {

const SIDE_LENGTH: u64 = 67_108_864;

let series = create_triangle_number_series(SIDE_LENGTH);

// sum the series and capture how long it took

let start = Instant::now();

let sum = sum_series(&series);

let duration = start.elapsed();

// compare our summed series against the "real" calculation

assert_eq!(sum, calculate_triangle_number(SIDE_LENGTH));

println!("{} µs", duration.as_micros());

}

Feel free to try different side lengths to see if the performance scaling is linear or not, or perhaps try to find a faster way to sum the series. In an upcoming article, we will be executing code loaded from a WASM module from within a host process written in Rust, but for now let’s build this and benchmark the performance.

Building Native and WASI

In order to compare the performance between native Rust and WASM, we need to build the code.

For native builds, simply run cargo build.

To run this outside the browser, we’ll need to compile our code to WASM with WASI.

For WASI builds, you can do one of two things:

cargo build --target wasm32-wasi- Use cargo-wasi, which essentially does the above

Please note that you may need to install the Rust target beforehand if you haven’t done so already: rustup target add wasm32-wasi.

If you recall from the introduction, we’re using WASI here as this WASM code is running outside the browser and needs the additional functionality provided by WASI to behave like a normal process.

Benchmarks

While we could run the program above many times and calculate statistics from the output, there is a better way.

criterion.rs provides a framework for executing benchmarks directly against the code and performing statistical analysis on the results.

But to do so, the code being benchmarked must be in a library and we must write the benchmarks themselves.

If you look at the repository for this project, you will see that the triangle number functions are in a library and the main function is in a bin package.

In the triangle-number package, there is a directory called benches that houses the criterion.rs benchmarks.

Let’s take a look at the write benchmark first.

This configures a benchmark called “write” that will repeatedly call create_triangle_number_series with 67_108_864 as the parameter for the side length.

Criterion will determine how many iterations are needed for statistically significant results.

The black_box() function prevents the compiler from being able to optimize the code in a way that prevents us from calling the function repeatedly.

pub fn criterion_benchmark(c: &mut Criterion) {

const SIDE_LENGTH: u64 = 67_108_864;

c.bench_function("write", |b| b.iter(|| create_triangle_number_series(black_box(SIDE_LENGTH))));

}

Next, let’s take a look at the “read” benchmark.

This time, it only calls create_triangle_number_series() once, then repeatedly calls sum_series() until enough data is collected.

pub fn criterion_benchmark(c: &mut Criterion) {

const SIDE_LENGTH: u64 = 67_108_864;

let series = create_triangle_number_series(SIDE_LENGTH);

c.bench_function("read", |b| b.iter(|| sum_series(&series)));

}

Running the benchmarks for native is a simple as cargo bench --release.

For WASI, it’s a little more involved.

Check the README in the repository for more details.

Results

Note: testing was done on a machine with an AMD Ryzen 7 5800X3D processor running Linux 6.6.10.

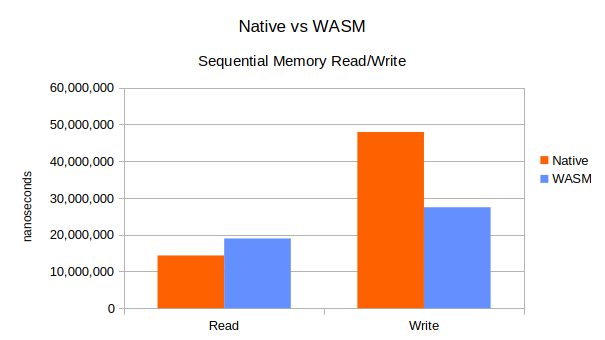

The table below shows the average time taken on each benchmark over hundreds of iterations. The results are in nanoseconds (1 millisecond = 1,000,000 nanoseconds). The standard deviation for WASM code was actually lower than native, but neither were significant enough for concern here.

| Native | WASM | |

|---|---|---|

| Read | 14,352,982 | 18,986,350 |

| Write | 47,957,622 | 27,466,182 |

The read benchmark indicates that WASM is ~32% slower than native code at sequential memory access.

The elephant in the room here is the poor performance by the native code on the write benchmark, coming in at ~75% slower than WASM.

Let’s take a closer look at the create_triangle_number_series() function:

/// Create a series that contains the integers from `1` to `side_length`

fn create_triangle_number_series(side_length: u64) -> Vec<u64> {

// `=side_length` makes the range inclusive

(1..=side_length).collect()

}

What I suspect is happening is that collect() is actually resizing the underlying vector as more entries are inserted.

If the memory allocation cannot be extended, then it will have to be reallocated and all of the data copied.

In WASM, where this code is running within a pre-allocated linear memory by itself, it probably can reallocate the vector’s memory in place consistently.

Another contributing factor could be the particular malloc implementations used by the system for native code versus the one provided by wasmtime.

Do I think WASM code is actually faster? No.

But I left this in here instead of rewriting the create_triangle_number_series() function to show the importance of benchmarking and the unusual problems that it can surface.

How would you change the function to bring performance back to expected levels?

With that out of the way, why should WASM be generally slower than native?

Any language that relies on a runtime environment inherently introduces some additional overhead.

Among other things, this can negatively impact caching efficiency on the processor since there is more code executing along with our program.

Another thing that could be causing some of this slowdown is if the runtime is having to check memory accesses to ensure they are within the WASM module’s permitted memory ranges.

As we will see in the next article, the WASM runtime allocates memory within the processes’ address space and requires all memory accesses from the WASM modules to be within that space.

To really see what’s happening we would need to profile the program using tools like perf, but that is out of the scope of this simple benchmark.

Conclusion

Strange benchmark results notwithstanding, the performance of WASM is quite impressive and is probably “fast enough” for most applications. The balance of speed and features indicates potential for a variety of use cases, from simulation systems to potentially any project benefiting from its sandboxing, cross-platform compatibility, and multi-language support. In the next article, we’ll take on Conway’s Game of Life, where we’ll explore not just WASM’s capabilities but also the nuances of its type system and memory model and how they impact application architecture.